How new fmcg brands bleed money undercutting competitors to survive in markets

Challenges in the FMCG business today

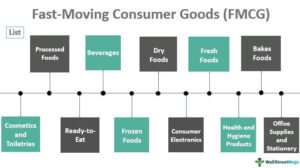

FMCG are the fast-moving non-durable customer goods that are produced and distributed for quick consumption, are high in demand, and are highly accessible due to their affordable prices. Therefore, these products have huge turnovers as it is produced and bought in huge masses and sold in the retail market at very affordable and competitive rates. Consequently, this sector holds a key position in determining the nations economy, making it the fourth largest sector of the Indian economy.

There is no set formula to this and this is a very vast subject for discussion. You need to be careful of the schemes / trade loads that you run in the market to support sales. Also you need to tightly control wholesale to keep the balance yet give them adequate margins.

Going overboard with any ATL BTL also causes imbalance. Check balances in place, that money given for BTL or other activities is not being diverted and misused in the market.

Competing with Giants: Survival Strategies for Local Companies in Emerging Markets

The FMCG industry has witnessed significant ups and downs in the pandemic. Markets and industries have been trying hard to meet new demands and restrictions and are trying to survive the deep waters. Hence, the hard-hitting lack of revenue has forced these industries to try to incorporate new strategies to thrive in the post-covid era.

Here are a few significant challenges the FCMG sector is likely to encounter in a post-pandemic era.

Aligning Assets with Fmcg Industry Characteristics

Retail Execution is a sales strategy aiming to improve sales in the store or venue of the brand by implementing specific regulatory measures. The distribution and display promotions contribute to a smaller chunk of sales, whereas retail executions are essential for driving sales to a higher level. Therefore, retail execution is challenging for (CPG)/(FMCG) companies. These companies, on average, lose more than 20% of the total sales opportunity and risk having products removed from store shelves due to retail execution issues.

Despite the heated rhetoric surrounding globalization, industries actually vary a great deal in the pressures they put on companies to sell internationally.

Even before the pandemic hit, the retail business was experiencing a gradual shift to an online-first business model. With the world’s digital turn, digitalizing field service in FMCG is of utmost importance for running a successful brand. Even the established and deep-rooted FMCG brands with many stores nationwide had to increase their online presence. It eventually became difficult to manage orders from various channels and ensure that the necessary stock was accessible at the closest sales point, a last-mile delivery partner, or a neighbourhood store near the customer’s residence.

Sales automation is essential as it provides an intelligent approach to customer satisfaction, end-to-end digitized sales scheduling and planning, and encourages a fulfilling customer experience.

FMCGs say can only tweak trade terms, but distributors demand margin parity

The All India Consumer Products Distributors Federation (AICPDF) has written a letter to over two dozen top consumer companies, including Hindustan Unilever, Procter & Gamble, Dabur, Marico, Godrej and Tata Consumers, urging them to not give preferential treatment to any channel on the basis of order volume, and instead offer equal margins to everyone.

Several consumer goods companies could only slightly tweak their terms of trade with organised wholesalers, such as Reliance, Metro Cash & Carry, Udaan and Walmart, after the country’s biggest distributors association threatened to halt supplies from the new year if their demands for product price-parity and equal margins are not met.

Two parameters—the strength of globalization pressures in an industry and the company’s transferable assets—can guide that company’s sales and marketing.

The proficiency in acquiring, storing and processing data is improving at an unprecedented rate, bringing about a data explosion. For example, brand tracking, weekly consumer sales, shopper data from friendly and well-compensated retailers, and hundreds of metrics previously existed in the FMCG world contingent upon which data/analytics association.

More than 90% of data generated and offered to anxious marketers and analysts are futile.

Instead, intelligent associations will buy pertinent data (manage data costs), conclude the proper linkages to consumer conduct, and efficiently use it to foster products, administer trade, and communicate well with customers.

Defending with the Home Field Advantage

For defenders Fmcg brands, the key to success is to concentrate on the advantages they enjoy in their home market. In the face of aggressive and well-endowed foreign competitors, they frequently need to fine-tune their products and services to the particular and often unique needs of their customers. Defenders need to resist the temptation to try to reach all customers or to imitate the multinationals. They’ll do better by focusing on consumers who appreciate the local touch and ignoring those who favor global brands.

Far from weighing down operations with low-margin sales, the company’s distribution network was the key to defending its home turf.Environment and sustainability

Associations that can demonstrate sustainability across their whole ecosystem will profit from good consumer bonding scores. However, the capacity to charge a premium to take care of inflated costs will remain restricted as buyers will progressively see sustainability as a given instead of an advantage to be managed by not many.

For would-be contenders that lack access to key resources, finding a distinct and defensible market niche is vital.

The trick for the FMCG companies for the old loyalty is to identify the audience they cater to.

Being the most aged sector, FMCG has a wide range of consumers, from senior citizens to millennials. This wealthier demographic places a higher value on simple, reliable, and risk-free products. The challenge for brands is to appear relevant to this ageing demographic while remaining “cool” enough to attract younger customers. Constantly evolving brand strategies and digitalizing while ensuring easy accessibility can help strike this balance.

Not only will managers find their strategies likely to evolve over time, but the nature of their industry may change as well.

The future of FMCG growth relies heavily on how well the organizations can amp up their facilities and serve the untapped Bharat.

Reliance’s FMCG entry into Ecommerce, the Nirma moment from the past.

In the 1980s, Nirma took on the might of Hindustan Lever, now known as Hindustan Unilever, and moved ahead of Surf to capture a significant market share. Nirma was priced 75% cheaper compared to Surf. In fact, Nirma’s success is also known to have forced Unilever and P&G to launch cheaper clones. After establishing its leadership in economy detergents, Nirma entered the premium segment, launching toilet soaps, Nirma beauty soap and Shuddh Salt.

Taking its private label range to general trade will challenge well-established foreign groups like Unilever, Nestle, P&G, Reckitt, PepsiCo and Coca-Cola and homegrown companies like Dabur, Emami, Marico, ITC, Godrej Consumer and Adani Wilmar, which last fiscal overtook Hindustan Unilever as India’s biggest FMCG company, clocking a revenue of Rs 54,214 crore.

Reliance will sell products like pulses and grains, edible oil, spices, biscuits, namkeens, ready-to-cook meals, ketchups, soft drinks, fruit juices, tea and coffee.

Brands in the food space include Good Life, Desi Kitchen, Snac tac and Yeah!. In the non-foods space, it has entered categories like soaps, face wash, hair oils, sanitisers, toothpaste, lipsticks, detergents, toilet cleaners and agarbattis. Brands here include Get Real, Puric, My Home, Enzo and Glimmer.

At 6%, Reliance is incentivising super stockists by offering double the margins compared to other FMCG companies.

So, can Reliance compete against entrenched players on the shelves of the country’s supermarket and kirana stores, the latter of which serve roughly 80% of the retail market?

Moving on, Reliance Retail is known to deeply undercut its rivals with its private-label FMCG brands which it currently sells at its Reliance Fresh and Reliance Smart supermarkets and hypermarkets.

Reliance Industries’ entry in the FMCG sector will heat up competition in the space dominated by the likes of HUL, ITC, Nestle India and Patanjali. Will Reliance be a disruptor in this segment too?

What is undercutting in FMCG?

What is the retail chemist’s cut in India

Medicines & Drugs have some of the highest retail margins in India. Any chemist in India typically gets the following in every product he buys to sell from his outlet:

Retail Margin – 10% to 30%. Varies from product to product.

Additional Discounts (popularly known as schemes) – This is over & above the Retail margin, & is given basis quantity purchased. This is similar to the Buy 2 get 1 free discounts we as consumers buy. It typically works out to an average of 5%-8%.

The branded shelves that you see in the shop – Chemists are paid display money or “Rent” for it. Average “Rent” is Rs. 300/- per branded window.

Now wholesalers get more margins because of the large quantities that they buy in. They also typically lose money on one product but make it up on the others. This is called “undercutting”. They do this to get rid of any old stock or more commonly with a product which has large sales volumes.

This “undercutting” practice is so prevalent that if you go to another wholesaler & negotiate, you can get a better deal. Depends on your negotiation skills.

Many in the FMCG industry can tell you with complete confidence that Indian retailers are really spoilt & they milk money. If you know what you are doing, open a Kirana shop OR a Chemist shop & you are set for life.

What are some of the brands that literally have little or no competition in the market?

There are some examples which fit into it –

In noodles category – Maggi is undisputed leader in India despite the controversy in India it has bounced back with many new flavors. People were literally waiting for the relaunch. Maggi relaunched through exclusively snapdeal, customers latched on to it.

Hygiene soap category: Dettol is the leader by far, no comparision.

Toilet cleaning category: Harpic is the leader.

In the high end phones i Phone still leads.

Chyawanprash – Dabur is the undisputed leader.

Fruit Juice category: Real Juice is the leader.

Butter, AMUL is leader in India.

Glucose biscuit category: Parle G.

Cookies biscuit category – Good Day.

Top end diesel Bikes – Royal Enfield

SUV in Rural India – BOLERO , no competition at all.

Maruti In Car segment in India at 47% market share, 2nd player Hyundai is at 17%. Maruti is leader by far.

What is the best approach to setting volume based price discounts for a product?

The following concepts can be kept in mind.

Purpose – This has to start with a point-0 because it is the most important step. The purpose of offering volume based discounts can be one of the following:

(a) Stock liquidation

(b) Generate Trials

(c) Grow Sales (or Grow sales during a particular period/season)

(d) Kill Competition

(e) If your objective is a combination of all the 4 points above then you don’t need to read this answer. You need luck.

Why knowing the purpose matters is because if you’re aiming for (a) Stock Liquidation – it is possibly because you’re finding the product difficult to sell in the regular scheme of things and you’d want to get rid of it ASAP. Yes, Inventory Costs are high. If this is the case then you would be better off focusing on your largest customers, possibly in isolated markets. Why? So that you can move the product in lesser number of sales and also so that the product-you-wanted-to-get-rid-of doesn’t circulate back to your primary/important markets through wholesale or passive distribution channels.

On the other hand, if generating trials (b) is your focus, then you’d rather be more focussed on enabling the smallest customers to purchase your product. Your Volume-Discount Tiers (explained later) would be start at much lower values.

If the objective is to grow sales (c) then you will necessarily have to start with observing and analysing the current buying patterns of customers across the board. Because to grow sales sustainably you not only need your largest customers to buy even more, but you also need the smaller ones to start buying medium to large quantities. A lopsided (focused solely towards larger customers/wholesalers) can lead to future demand drops and price instability.

Finally, if the objective is to (d) Kill Competition then you should focus on cornering the market. This would require information not only on your product’s purchasing patterns but also some information about that of the competition’s.

Hopefully, you will be knowing what you main objective is going to be before you start planning out the volume based discount.

Basic concepts used all through Fmcg History to bear in mind.

Volume-Discount Tiers – You would most typically be publishing a trade discount in tiers. For e.g. 1-10 pcs gets 5%, 11-20 pcs gets 6%, etc. The entire idea behind tiers is:

“Get more people to buy more stuff.”

(a) Basically you want to enable more people to avail discounts – and hence have an incentive to purchase your product.

(b) You want to give incentive to buyers who purchase an average of ‘x’ units per period so that they purchase ‘x+n’ units during the period in which the discount is applicable. To achieve this, you need to look at all available transaction/sales data and figure out which tiers to put discounts for and the actual discount value for those tiers. For e.g. a customer might be happy getting a 10% discount off a Rs.100 purchase (net saving Rs.10). However, a customer might not see great incentive in a 11% discount off a Rs.1000 purchase (net saving Rs.110).

Market Price Stability – You don’t want bigger customers (or wholesalers) to stock up on your product during the discount period and then drop market prices and sell to retail/consumers at lower prices. You would want the discount to be high enough to encourage the purchase, but low enough to keep them from viably undercutting prices at a later stage.

Trade Loading – This is a pattern represented across wholesalers who stock up during discount periods to avail the highest discounts in the highest tiers and then cut down purchase completely and keep liquadating stocks gradually. Wholesalers may not undercut and distort market prices, but even a small number of such over-stockers will lead to a huge spike in sales followed by an abysmal dip. Becomes difficult to explain in Quarterly Reviews – from a salesperson POV.

Blocking Competition – However, trade loading can be avoided if your product market has any seasonal variations in consumption. In fact, it can be used to counter competition. Ideally you would like to start the discounts sufficiently before the “season” begins for your particular product. In this way, by the time the “season” begins the trade is already loaded with your product keeping competition out. Also, because trade started stocking up on your product before the “season” it would be totally normal for them to liquidate the stocks during the season – although it might lead to some price instability.

Period Schemes – In stead of running a volume discount for a single transaction/purchase, it could be done for an entire period. Consider a 3 month period, with minimum qualifying purchase value criteria for each month and a final criteria for the overall 3 months. Slightly complex, yes, but it will help solve a lot of issues related to trade-loading and market price stability.

Communication – This is one of the most important aspects of a discount/promotion. The communication has to be simple, recurring at regular intervals throughout the scheme period and should highlight a clear benefit or ROI.

What stops people from starting companies and undercutting competitors if it’s a relatively easy market to get into?

How is Colgate still successful despite the many brands that came out in the market?

William Colgate (his name is the toothpaste’s, not the other way round) created a starch, soap, and candle business in New York with Francis Smith.

1873: Get dental

Colgate starts selling aromatic toothpaste in jars.

Source: First Versions

1896: Out of the jar, into the tube

Colgate introduces toothpaste in a collapsible tube. (Getting to a familiar form now)

Source: Colgate-Palmolive Website

1908: New tube, who dis?

Colgate & Company gets incorporated by the five sons of Samuel Colgate. The ribbon opening is added to the toothpaste tubes in the same year. The slogan “We couldn’t improve the product, so we improved the tube.” was created to highlight this development.

Source: WorthPoint

Thus, by 1937, when Colgate first entered the Indian market, it had already gathered over a century’s worth of intel, operating on foreign grounds.

Here’s what the company learned and how they used this information.

High stature starts

Colgate didn’t have it easy following its entry into the Indian forum. Pre-existing Indian brands that knew the playing grounds wouldn’t make it easy for a foreign entrant. But how did Colgate thrive, and has been, since? Well, here’s Colgate’s business model since its touchdown in India.

“Mouth” marketing

On its entry to India, Colgate was met with stiff competition by Dabur. This brand had already established itself in India and was selling well because it was ayurvedic (and we all know that we Indians love us some Ayurveda). But the paste, had really poor taste. (ba-dum-tss + facepalm) Colgate turned this gustatory need into a driving point for its sales. Most toothpaste brands created what was basically an abrasive ointment for teeth.

But Colgate brought the revolutionary idea of “non-druggy tasting” toothpaste. All age groups could appreciate the better taste, but kids liked it the most. We’ve either been the kid or dealt with a kid that’s always fussy about brushing. Well, this problem has existed for a long time, and Colgate knew it could capitalize on this minor inconvenience.

Generous to consumers

Colgate might have revolutionised toothpaste by changing its taste, but a revolution only becomes so when it is backed by the masses. A revolution is just a new, maybe a good idea without the masses. Thus, to rally the masses, Colgate had to do something. So they went to the most unlikely segment of its target demographic; young, schoolgoing children with no purchasing power. But the approach wasn’t aimed at them as much as through them.

The children were actually a medium to reach the actual buyers; the parents. The anecdotal tale in the intro to this blog wasn’t a sham but a real story, and so was the marketing strategy. With the Oral Health Month campaigns started in 2004, Colgate has regularly reached out to schools and dental hygienists alike to maintain a brand recall value as “the toothpaste brand that kids like.”

These visits had a rather beneficial but funny side effect brought to my attention by a superior when discussing the whole “toothbrush, toothpaste aur sticker mila” phenomenon. While the excited kids acted as messengers of Colgate to their parents, the unruly ones that might have thrown the tubes away acted as yet another marketing tool as the tubes strewn on the road would still expose people to the brand.

Advertising through waste, that’s a first.

Ungenerous to competitors

While Colgate’s been massively successful and well-reputed due to its generosity with its customers, the competitors get a much more uncompromising attitude. This is one thing it does that is pretty mischievous. Colgate is that one person in any group project who does none of the work but gets away with being greatly credited for presenting it well to the concerned audience; the person who gets all the laughs for retelling an unheard joke.

Colgate works smart and lets its competitors work hard. Colgate might have established its dominance in the toothpaste industry by taking out the major players with the taste benefit in India; that was about all the advantage it gave itself. Colgate had captured a significant market share and started playing the safe game with this benefit.

This safe game entailed Colgate partially giving up on market research. Having captured the majority market share, Colgate gave itself a nice cushioned lead that it wasn’t risking. Giving up on market research sounds a bit extreme and a little… stupid, doesn’t it? Well, that’s because it is, which is why Colgate only stopped engaging in the risky aspect of market research, i.e., experimenting with new products, trying new innovations. “But Colgate has a wide variety of products, how did they come to be?” you might ask.

This is where the group project metaphor becomes a reality. You see, Colgate’s peers in the toothpaste industry are often the innovators, as entrants in a niche segment or existing brand diversifying its product range. Colgate watches these competing products and their performance, picks a winning horse, and beats it at its race. Voila! And when Colgate enters the race, it’s in it to win it. Once Colgate sets its sight on a toothpaste type, it makes sure the customer ends up using only Colgate’s version of it; this goal is accomplished by:

Undercutting prices achieved by saving on R&D and waste due to failed innovations.

Greater reach due to longer existence compared to competitors. This reach isn’t just in terms of general geographical spread but also store types. While most kinds of toothpaste appear either in drugstores or general grocery stores, Colgate and its various subcategories have a more “People’s product” feel to them, which is why they appear on both of the shelves.

As a result of this competitive behaviour, Colgate might often appear to be losing its lead, but the step back is for more of a run-up to overtake the competitors than “falling behind” as it takes away whatever share its competitors garner with their own research.

The premium experience- A new frontier

Toothpaste as a product was very tunnelled as just “oral care.” However, oral care was not as simple as it appeared. Premiumisation means producing exclusive products of a subtype in the existing market. For the toothpaste product line, premiumisation meant the creation of toothpaste that catered to particular needs, such as; sensitivity, whitening, diabetic care, enamel care, etc. The potential for premiumisation existed, which would mean each player could give themself an edge to outperform their competitors.

Premiumisation= Dollar Euro Yen Dinar Rupee, right? Well… For a little bit, yes. There were two types of operations in terms of premiumisation.

New entrants into the market for niche uses (the entire Sensodyne line, Patanjali’s ayurvedic paste),

Companies that already existed and were introducing a new line of products for the target niche (Himalaya’s sensitive paste, Dabur’s Babool Ayurvedic paste).

The companies engaging in premiumisation enjoyed the benefit they earned because of the “new shiny” effect. But Colgate would tug the rugs from under them promptly before they gained too much influence. Colgate would achieve this with its better brand recognition and competitive pricing.

Slow and steady, wins dominates the race.

A lasting, nostalgic impression

An economic moat is a competitive advantage that a company has over its competitors. Each player needed an edge as the toothpaste industry had multiple players with a wide variety of products. In the FMCG Industry, where Colgate is a big mogul, switching cost is not a moat or advantage companies can exercise very well.

Switching costs are the monetary and otherwise hindrances that a customer faces when switching from one brand to another within the same industry. However, switching is neither costly nor overly tricky for toothpaste.

You just buy a different brand whenever you like, but you don’t, like a lot of people, ever wondered why?

The reason behind this customer loyalty is the “Mouth Marketing,” and the “Generous to consumers” points combined. Through the giveaway, Colgate became a personal experience for the kids as consumers that grew up using the brand to the point where Colgate became the verb that replaced brushing for many. Similar to “Maggi” becoming the product name for noodles.

Is the FMCG industry slowing down?

Sure Nielsen does estimate 2019 pace of growth to be slower – a pace of 11–12%, one or two percentile points lower than the last few years ; and clearly this tighter demand is getting reflected in recent results of many of the FMCG majors.

However, FMCG in India is no way slowing down.

(Image Source : BCG)

Long term outlook is absolutely strong and will probably grow at a 12 to 14% pace until 2025.

A number of significant demographic changes will be driving this growth :

Real Incomes : Average household incomes are expected to increase by over 70% by 2025.

New entrants to workforce : More than a 100m people are estimated to enter the workforce through this period.

More households due to nuclearisation : Smaller families is an increasing trend, and at least 10m new households will be added .

Continous increasing urbanisation.

More Elite Households : House holds with over 10lac income will start to contribute over 48% of consumption, up from current 20 levels > driving premiumisation.

Top most festival Products FMCG consumers search today

World Wide Festive Trends Decoded What Indian festive consumers seek...

Read MoreHow right selection of FMCG Salesmen improves brand market share

How can FMCG Companies improve salesman’s technique in order to...

Read MoreHow most searched Fmcg sales and marketing words help newbie salesman

Why undestand FMCG sales management? Sales management is the process...

Read MoreHow Successful FMCG Salesman Starts his Day, a guide

How does one become a good sales executive in the...

Read More

Pingback: Understanding Beauty Cosmetics Skin Care Products Routine